Reversion to the Mean

I believe in timeless advice. Whether we admit it or not, there are some things that we learn through the years (typically from a parent or grandparent) which stand the test of time. The power of compound interest comes to mind. So does the suggestion of buying a home, rather than renting. As we all know, when you are done renting, you have nothing. Whereas, if you buy a house with a mortgage, then all those payments create equity/ownership over time. Why then, are so many companies deciding to pay rent for their enterprise software? Are they defying timeless advice?

***

Jeremy Grantham is one of the greatest investors in modern times. He is the cofounder and chief investment officer at Grantham Mayo van Otterloo (GMO), which has over $100 billion in assets under management. His investing philosophy is based on a simple truth that he has observed: markets always revert to their long term averages. Grantham calls this phenomenon Reversion to the Mean, and GMO will often take positions betting on this phenomenon, when asset prices deviate from their historical ranges.

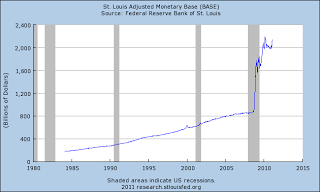

We sit in the midst of the largest debt driven credit bubble in the history of finance. As the Federal Reserve has aggressively expanded the money supply, there is an unprecedented amount of cash sloshing around the system.

David Einhorn, in his oft quoted talk at the Buttonwood Gathering, described it as follows:

"My point is that if one jelly donut is a fine thing to have, 35 jelly donuts is not a fine thing to have, and it gets to a point where it's not a question of diminishing returns but it actually turns out to be a drag. I think we have passed the point where incremental easing of Federal policy actually acts as a headwind to the economy and is actually slowing down our recovery, and I am alarmed by the reflexive groupthink of the leaders which is if we want a stronger economy, we need lower rates, we need more QE and other such measures."

Quick translation: too much of anything can become a bad thing, and right now, there is too much cash, too little interest earned on cash, and that is creating a cascading set of events.

Jamie Dimon, in his annual letter to shareholders, appropriately pointed out that all of this cash in the system has resulted in corporate cash balances increasing to 11.4% of assets, up from 5.2% in 2000. In a cash rich world, everyone is hoarding cash.

***

So, what does this mean for corporations? As any economist will tell you, the problem with too much cash, is finding a way to put it to productive use. And, ironically, despite the large amounts of cash in the system, every company that I visit has no or limited money for new projects. It's survival of the fittest, fighting for the few precious dollars available. But, how can this cash scarcity co-exist with the macro data? Well, the fact is that the cash is in the companies, but it's tucked away on the balance sheet (see Dimon comment above). When a company wants to avoid spending cash in the short term, this is when you see a shift from Capital Expense (capex) to Operating Expense (opex). Said another way, there is a decision to rent instead of buy. Let's check the definitions that I recall from my days of studying finance and economics:

Capital Expense

These are large projects requiring significant investment of cash. They are expected to help generate revenue or reduce costs for more than a year. Assessing capex is a matter of a) assessing the initial outlay, b) projecting future cash flows, and c) evaluating the future cash flows to assess ROI.

Operating Expense

These are costs not directly related to making the core product or delivering the core service of the enterprise. Opex is NOT variable (like materials) and instead, they tend to be fixed in the short-to-mid term.

So, why are companies trying to move everything from Capex to Opex?

***

Corporations have decided that they have something better to do with their cash than invest in new projects: they want to buy back stock. Some recent testaments to this fact:

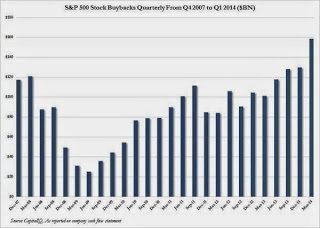

In aggregate, in the first quarter alone, companies spent a record $160 billion on stock buybacks. Best viewed in a chart:

Companies have spoken. This is how they want to use their cash for now. Is this a new normal or will there be a Reversion to the Mean?

***

Clay Christensen interviewed Morris Chang, the founder of TSMC, awhile back, asking about companies that refuse to spend capital. Clay said to Chang, “Every time a new customer outsources to you, he peels assets off of his balance sheet, and in one way or another puts those assets on your balance sheet. You both can’t be making the right decision.”

“Yes, if you measure different things, both can be right,” Chang replied. “The Americans like ratios, like RONA, EVA, ROCE, and so on. Driving assets off the balance sheets drives the ratios up. I keep looking. But so far I have not found a single bank that accepts deposits denominated in ratios. Banks only take currency. There is capital everywhere,” Chang continued. “And it is cheap. So why are the Americans so afraid of using capital?”

The answer to Chang's question is that companies are choosing to spend it another way. But, lets look at a simple example of what happens, when a company makes this decision. Here is a simple example (based on real events) of a company that needs to acquire $5 million of supply chain software to run their business. Option 1 is when the company rents the software (an Opex model), while Option 2 is when the company uses Capex to fund the project.

This company chose Option 1. Option 1 is a poor financial decision for the company, granted it may be good from the narrower view of the purchaser. But, what happens when this cumulates across a company? If this same decision was made 10 times in a company, suddenly they have boat anchor of $30M/year of Opex. And, as mentioned above, this is fixed in the mid-to-short term.

***

The obsession with Opex is not sustainable. This is not a viable way for companies to grow their cost base. That being said, it's happening due to the cash excess driving stock buybacks and other uses of money. A recent JP Morgan Chase report stated, "the other side effect of elevated dividends and share buybacks is that these distributions to shareholders may reduce the long term potential of the company to grow relative to the alternative of capital spending."

As Grantham would do, I'm betting on a Reversion to the Mean. At least, that's what timeless advice would tell me to do.

***

Jeremy Grantham is one of the greatest investors in modern times. He is the cofounder and chief investment officer at Grantham Mayo van Otterloo (GMO), which has over $100 billion in assets under management. His investing philosophy is based on a simple truth that he has observed: markets always revert to their long term averages. Grantham calls this phenomenon Reversion to the Mean, and GMO will often take positions betting on this phenomenon, when asset prices deviate from their historical ranges.

We sit in the midst of the largest debt driven credit bubble in the history of finance. As the Federal Reserve has aggressively expanded the money supply, there is an unprecedented amount of cash sloshing around the system.

David Einhorn, in his oft quoted talk at the Buttonwood Gathering, described it as follows:

"My point is that if one jelly donut is a fine thing to have, 35 jelly donuts is not a fine thing to have, and it gets to a point where it's not a question of diminishing returns but it actually turns out to be a drag. I think we have passed the point where incremental easing of Federal policy actually acts as a headwind to the economy and is actually slowing down our recovery, and I am alarmed by the reflexive groupthink of the leaders which is if we want a stronger economy, we need lower rates, we need more QE and other such measures."

Quick translation: too much of anything can become a bad thing, and right now, there is too much cash, too little interest earned on cash, and that is creating a cascading set of events.

Jamie Dimon, in his annual letter to shareholders, appropriately pointed out that all of this cash in the system has resulted in corporate cash balances increasing to 11.4% of assets, up from 5.2% in 2000. In a cash rich world, everyone is hoarding cash.

***

So, what does this mean for corporations? As any economist will tell you, the problem with too much cash, is finding a way to put it to productive use. And, ironically, despite the large amounts of cash in the system, every company that I visit has no or limited money for new projects. It's survival of the fittest, fighting for the few precious dollars available. But, how can this cash scarcity co-exist with the macro data? Well, the fact is that the cash is in the companies, but it's tucked away on the balance sheet (see Dimon comment above). When a company wants to avoid spending cash in the short term, this is when you see a shift from Capital Expense (capex) to Operating Expense (opex). Said another way, there is a decision to rent instead of buy. Let's check the definitions that I recall from my days of studying finance and economics:

Capital Expense

These are large projects requiring significant investment of cash. They are expected to help generate revenue or reduce costs for more than a year. Assessing capex is a matter of a) assessing the initial outlay, b) projecting future cash flows, and c) evaluating the future cash flows to assess ROI.

Operating Expense

These are costs not directly related to making the core product or delivering the core service of the enterprise. Opex is NOT variable (like materials) and instead, they tend to be fixed in the short-to-mid term.

So, why are companies trying to move everything from Capex to Opex?

***

Corporations have decided that they have something better to do with their cash than invest in new projects: they want to buy back stock. Some recent testaments to this fact:

Darden Restaurants sells Red Lobster to Golden Gate Capital for $1.6 billion, promising to use $700 million to buy back stock.

Cisco Borrows $8 Billion in Bond Sale to Help Finance Buybacks

Microsoft Plans $40 Billion Buyback

Oracle Approves $12 Billion Buyback

And, IBM, has done a fair share of buybacks

In aggregate, in the first quarter alone, companies spent a record $160 billion on stock buybacks. Best viewed in a chart:

Companies have spoken. This is how they want to use their cash for now. Is this a new normal or will there be a Reversion to the Mean?

***

Clay Christensen interviewed Morris Chang, the founder of TSMC, awhile back, asking about companies that refuse to spend capital. Clay said to Chang, “Every time a new customer outsources to you, he peels assets off of his balance sheet, and in one way or another puts those assets on your balance sheet. You both can’t be making the right decision.”

“Yes, if you measure different things, both can be right,” Chang replied. “The Americans like ratios, like RONA, EVA, ROCE, and so on. Driving assets off the balance sheets drives the ratios up. I keep looking. But so far I have not found a single bank that accepts deposits denominated in ratios. Banks only take currency. There is capital everywhere,” Chang continued. “And it is cheap. So why are the Americans so afraid of using capital?”

The answer to Chang's question is that companies are choosing to spend it another way. But, lets look at a simple example of what happens, when a company makes this decision. Here is a simple example (based on real events) of a company that needs to acquire $5 million of supply chain software to run their business. Option 1 is when the company rents the software (an Opex model), while Option 2 is when the company uses Capex to fund the project.

This company chose Option 1. Option 1 is a poor financial decision for the company, granted it may be good from the narrower view of the purchaser. But, what happens when this cumulates across a company? If this same decision was made 10 times in a company, suddenly they have boat anchor of $30M/year of Opex. And, as mentioned above, this is fixed in the mid-to-short term.

***

The obsession with Opex is not sustainable. This is not a viable way for companies to grow their cost base. That being said, it's happening due to the cash excess driving stock buybacks and other uses of money. A recent JP Morgan Chase report stated, "the other side effect of elevated dividends and share buybacks is that these distributions to shareholders may reduce the long term potential of the company to grow relative to the alternative of capital spending."

As Grantham would do, I'm betting on a Reversion to the Mean. At least, that's what timeless advice would tell me to do.